Making Anna

Our team undertook documentary strategies to ensure that the details of the animation were as historically accurate as possible. We compiled a database of images and contextual information for each scene containing references and examples of local buildings, structures, tools, utensils, clothing, and hair styles. Here, we break down the animation process and the decisions we made about how to portray Anna's world.

How did you discover the true events of this story?

William G. Thomas III: The story was well known and reported at the time. Several historians have written about and referred to Anna's story, including Terri Snyder, Robert Gudmestad, Edward Baptist, and others, but historians did not know what happened to Anna. In 2015 at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., we were researching the case files of enslaved people who petitioned for their freedom, and we stumbled on the records of Anna's lawsuit. We put the case online at earlywashingtondc.org. A fellow scholar, Candace Carter, an art historian at Stanford, was researching Anna's story, and contacted us about the case. Carter, Kaci Nash, and the rest of our team began putting the pieces of her story together. Together in conversation, we concluded that Anna, the enslaved woman, and Ann Williams, the plaintiff in the freedom suit, were the same person. No one knew that she had sued for her freedom. The National Archives also held in its special vault the records of the Congressional inquiry about Anna's case. Francis Scott Key, Anna's attorney, testified before the committee, as did the doctors that treated her. When we put all of this new evidence together, we had a much different story to tell about Anna than had previously been told.

What part of Anna's story most resonated with you?

Kwakiutl Dreher: The very fact that she had the spirit to tell her story. There is a power in storytelling, and we see that with Anna. There is a risk to telling stories. This woman had just jumped, she could have died, and she was bought for $5. Instead of keeping quiet, she tells her story. It fiercely complements the actions she took.

Will: The resilience of the human spirit. Anna's story gives us an unflinching look at slavery even as it shows us how enslaved people made a way out of no way. This was the beginning of the interstate slave trade in the U.S., a chapter in our history many Americans have forgotten. Over a million men, women, and children were sold from Maryland and Virginia. Families were broken up and people transported to the cotton and sugar fields in the Deep South. We need to face this history.

What kind of research did you do?

Kwakiutl: We thought a lot about skill and a legacy that might have been passed down from Anna's mother and also from Africa. Enslaved people weren't stripped of everything. They brought a lot of what they knew with them and carried it out. Benin weavers had upright looms, and were highly skilled. We wanted to show that deep history, and what her past, her craftsmanship, might have meant.

Will: We looked not only at the court records but also the testimony of ex-slaves from Maryland, particularly from Prince George's County. These narratives clearly show us that every aspect of slavery was present in Maryland—whipping, terror, deception, and cruelty. We should have no illusions that slavery in Maryland was somehow less severe than elsewhere. A number of the scenes in Anna were drawn directly from the evidence in these records.

Michael Burton: We worked hard to ensure that the details of the animation were as historically accurate as possible. We compiled a database of images and contextual information for each scene containing references and examples of local buildings, structures, tools, utensils, clothing, and hairstyles. We actually built a counterbalance prop loom so that the actors could act in a genuine way at the loom—we wanted their body mechanics to be as true to the period as we could make them.

Why did you choose animation to tell this particular story?

Kwakiutl: We wanted to tell Anna's story from her perspective and from the perspective of an enslaved person, avoiding common tropes and bringing the viewer into her everyday life. Animation allowed us to imagine Anna's world as she saw it and maybe how she experienced it.

Mike: As an example, our second scene is a crane shot that shows a medium-sized plantation from above. As the camera drops down, we enter the living quarters of the enslaved and quickly truck into a loom house where a young Anna is learning to weave from her mother. We felt this approach would make Anna and her husband Edward more familiar and ultimately more human.

What was the animation process like?

Mike: Anna is a rotoscoped animation, meaning that we first filmed actors in costume, then traced over every other frame of the footage with acrylic or digital paint, then overlaid each of the animated characters onto a background painting. Nine animators worked over the course of a year and a half to animate each scene. I acted as lead animator, director, and producer. As lead animator, I wanted to create a distinct style that drew on early nineteenth-century etching techniques to create a kind of lifelike version reminiscent of that earlier style.

The sketch on the left provided the production team (Hannah Ayers and Lance Warren) with instructions for where to position their camera and where the actor portraying Edward would need to stand. These are called marks and show actors what will happen in the shot. The right side shows the final animated result.

Like the previous image, this sketch provided actress Margarette Joyner information on how she would need to fall and how it would look on screen. This also provided the entire team an opportunity to see what was possible and how the action would read on screen.

This sketch illustrates the intended edit. In the final sequence, we begin with a wide shot that cuts to a close-up of Anna's fall. Shooting both wide and close formats provided the editorial team with the flexibility to create a more dramatic effect when cutting the scene.

This sketch shows a tightly-framed camera angle, known as the hero shot, capturing the moment Anna and Edward fall in love.

These images showcase some of the student animators who participated in the film's post-production process. Included are images from a visit from the film's composer, Khris Royal, who met with the team to learn about the production.

Imani Brown (right) and Thalia Rogers (left) in one of the animation studios.

Ryan Neimeyer rotoscope-paints a scene from the film by tracing a frame from the footage onto glass, then captures each frame with a DSLR camera using a stop-motion software called Dragonframe.

Another angle reveals that the glass Ryan paints on sits over a green lit box, making it easier for the team to key out the background and reveal only the painted surface image.

Madison Svendgard completes the same process on another scene.

Brian Coate completes the same process.

Some of the post-production team with co-producers and composer Khris Royal. From left to right: Michael Burton, Brian Coate, Imani Brown, Skylar Simpson, Kwakuitl Dreher, Khris Royal, and William G. Thomas III.

Skylar Simpson shows Khris Royal how the process of animation takes place.

Skylar Simpson animates a scene of the film.

Brian Coate explains how he produces animated sequences for each scene to Michael and Khris.

Brian Coate explains how he produces background environments for each scene.

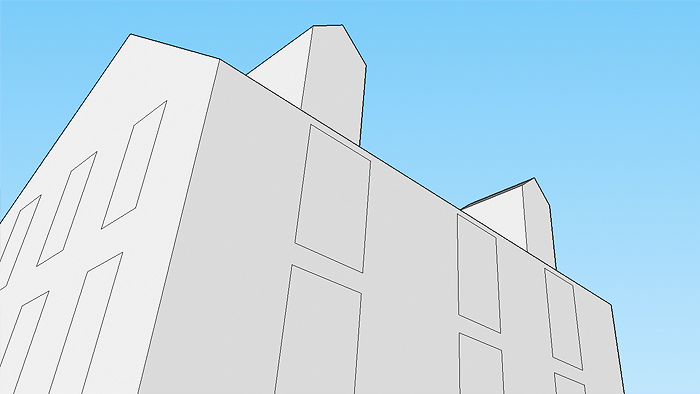

The Plantation of the fictional Coleridge Family

Concept Art

Illustrating the fictional Coleridge Plantation posed two distinct problems: creating an environment that is recognizable as a plantation while avoiding the conventions often used in movies about slavery, and understanding what that environment looked like relative to the socio-economic conditions of the early 1800s.

Research

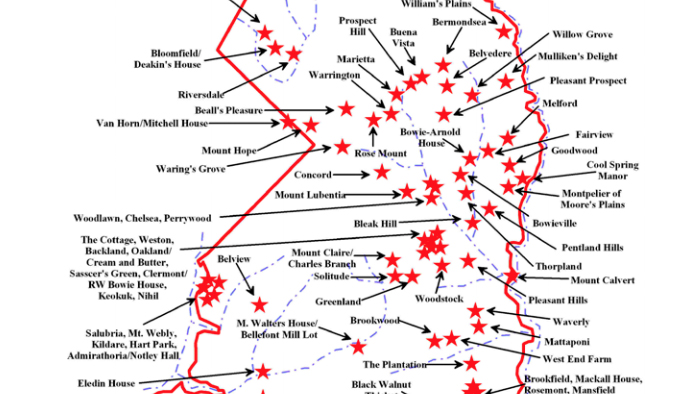

The animation team was able to create a realistic composite based on the descriptions of several Maryland plantations. The team drew heavily on the scholarship of William G. Thomas III and a document titled Antebellum Plantations in Prince George’s County, Maryland, which describes most of the plantations in the state in order of size.

The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, Antebellum Plantations in Prince George’s County, Maryland (2009), 106.

Final Animation

The team chose an aerial view of the plantation that tracked down to enter Anna's world via the slave quarters of an average-sized Maryland plantation circa 1800.

Final Animation

The aerial view tracks down to the quarters of the enslaved inhabitants of the Coleridge Plantation.

Final Animation

There were a few brick Federal structures in Prince George's County, including Gabriel Duvall's Marietta, but we decided to portray Coleridge as a middling planter, one who perhaps aspired to but had not achieved the wealth necessary to construct a brick mansion. Instead, his dwelling, while still substantial, was a more modest wood frame house.

The Loom House of the fictional Coleridge Plantation

Reference Photo

A slave cabin at Sotterley Plantation in St. Mary's County, Maryland, served as the inspiration for what the structures on our Maryland plantation looked like.

Historic Sotterley Plantation, Facebook, January 7, 2015.

Reference Photo

The interior of the slave cabin at Sotterley Plantation in St. Mary's County, Maryland, offered a view of the cramped space the enslaved had to live and work in.

Historic Sotterley Plantation, Facebook, April 1, 2015.

Reference Photo

A slave cabin at Prestwould Plantation in Mecklenburg County, Virginia. Although this plantation was far bigger than the mid- to small-sized plantation we believe Anna lived and worked on, archaeological research of the site provides details such as pile locations, chimney placements, and exterior treatments.

"Prestwould slave quarter under restoration" in Patricia M. Samford, Archaeological Investigations of the Prestwould Slave Quarter, Mecklenburg County, Virginia (44MC534), Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series (2001), 6.

Final Composite Scene

The final composite shot, based on the reference photos and archaeological information on slave quarters.

Reference Video

A video produced by George Washington's Mount Vernon provided a sense for how a counterbalance loom would have been used to produce linen. We assume this method was common for the production of fabrics throughout the region. It is widely understood that skills like weaving, blacksmithing, and horseshoeing were passed down from generation to generation.

George Washington's Mount Vernon, "Weaving on Mount Vernon's 18th Century Loom," YouTube, October 21, 2013.

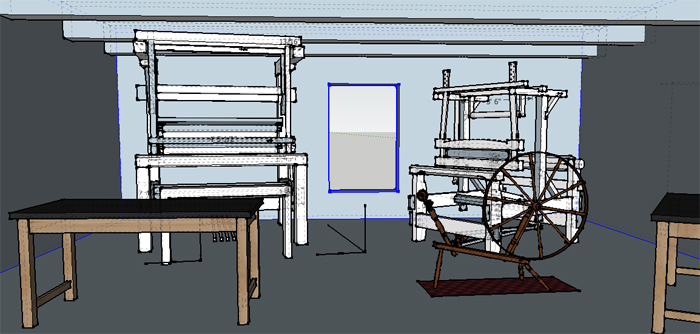

3D Model

Michael Burton created a 3D model of a loom house using looms created by users of the SketchUp 3D Warehouse. This model gave Burton the ability to select the best angles to shoot live actors using a reconstructed loom.

Reconstructed Loom

A loom constructed for the live video shoot.

Filming

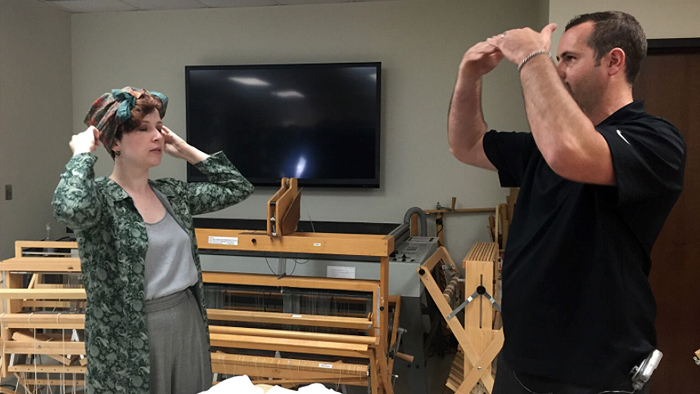

Actress and screenwriter Kwakiutl Dreher taking direction from Michael Burton as she portrays Anna's mother, Nan.

Rotoscope Animation

Live action footage being rotoscope animated (top) and the final composited image (below).

Clothing

Reference Art

A nineteenth-century artist's rendering of enslaved women's clothing used as inspiration for the look of Anna.

Female Clothing Styles, Paramaribo, Suriname, ca. 1831, as shown on slaveryimages.org, compiled by Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite and sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

Reference Art

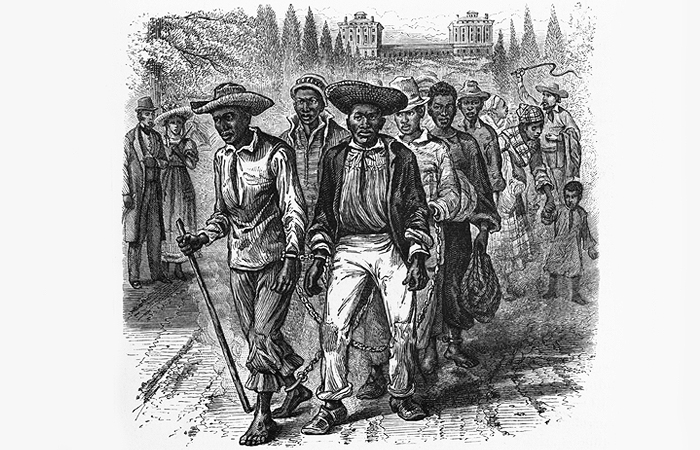

A wood engraving depicting a scene from 1815 Washington, D.C., used as inspiration for the clothing worn in the film.

"A slave-coffle passing the Capitol. Washington D.C.," in A Popular History of the United States (New York: Scribner, Armstrong, and Company, 1876-1881), Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Costume Detail

A dress created for the film by Nicole Rudolph, a graduate student in the Department of Textiles, Merchandising and Fashion Design at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Costume Detail

Detail of a dress created for the film by Nicole Rudolph.

Costume Detail

A petticoat created for the film by Nicole Rudolph.

Costume Detail

A child's coat created for the film by Nicole Rudolph.

Costume Detail

Pleating detail on a dress created for the film by Nicole Rudolph.

Costume Research

Nicole Rudolph discussing clothing fit with Michael Burton. Rudolph worked as a seamstress in Colonial Williamsburg for eight years. She specializes in 19th century costume for theater and film.

Costume Research

Nicole Rudolph advising how actresses in Nebraska and Virginia should wear hair wraps.

Costume Research

Nicole Rudolph shows Michael Burton a variety of reconstructed clothing from the early 1800s.

Hair

Reference Art

A painting of a scene observed by architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe through a tavern window in Norfolk, Virginia, was used as inspiration when determining the look of Anna. We made a conscious effort to be true to the time period and the personal importance enslaved people placed upon styling their hair.

Barbers, Norfolk, Virginia, 1797, as shown on slaveryimages.org, compiled by Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite and sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

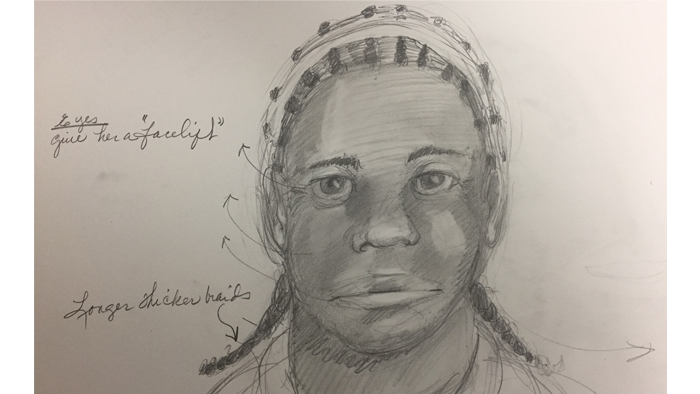

Concept Art

A sketch of what Anna might look like.

Michael Burton, William G. Thomas, Kwakiutl Dreher, and Kalari Flotree worked through the concept and look of Anna, paying attention to the features of people from the Chesapeake region.

Sketch by Michael Burton.

Concept Art

A sketch with further revisions used to complete the style sheet of Anna, used to help identify the actress who would portray her.

Sketch by Michael Burton.

Screen Test

Actress Margarette Joyner in a screen test.

Final Costume and Hair, Live-Action

Actress Margarette Joyner in front of a green screen at Bridge Studios in Richmond, Virginia. Here, she is dressed in the garments made by Nicole Rudolph.

Final Costume and Hair, Rotoscope Animation

Anna fully rotoscope animated and set into the scene in the garret of the tavern on F Street.

The Streets of the Nation's Capital

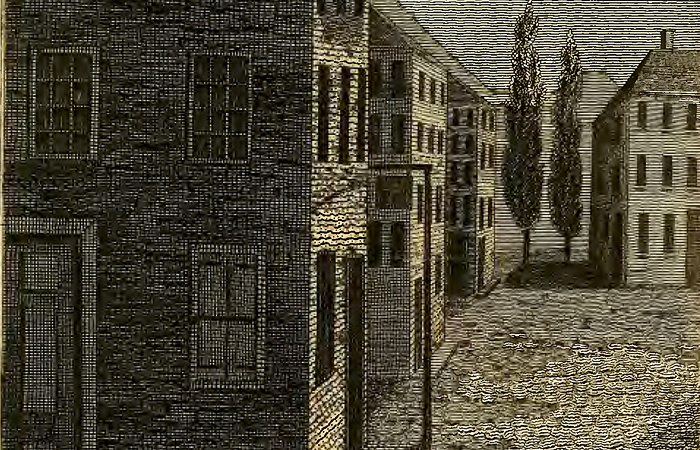

Reference Art

This etching by Alexander Rider published in 1817 provided the animation team with visual information about the F Street area and Pennsylvania Avenue.

Jesse Torrey, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery in the United States (Philadelphia, 1817), facing 43.

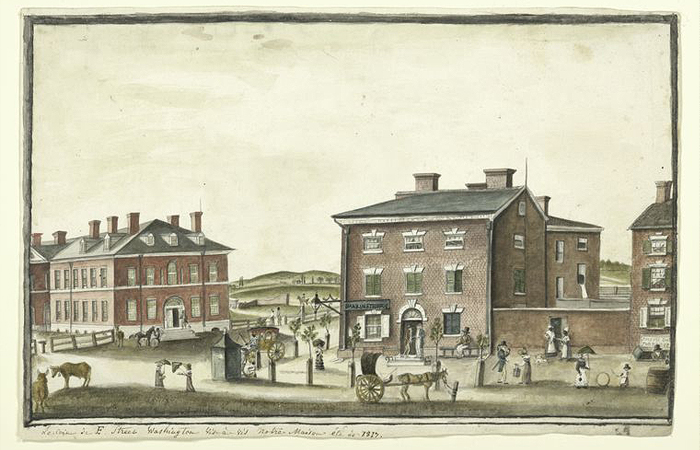

Reference Art

This 1817 watercolor painting of the corner of F Street and 15th Street by Anne-Marguérite, Baroness Hyde de Neuville, provided more information about the style and locations of the surrounding buildings.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library, "Le coin de F. Street Washington vis-à-vis nôtre maison été de 1817," New York Public Library Digital Collections.

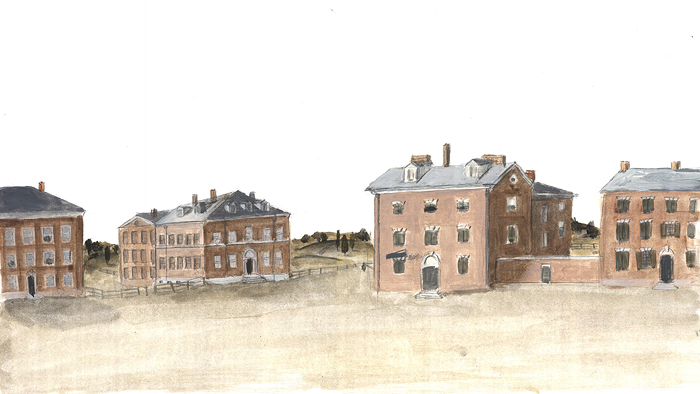

Reference Art

Our reproduction of the Hyde de Neuville painting.

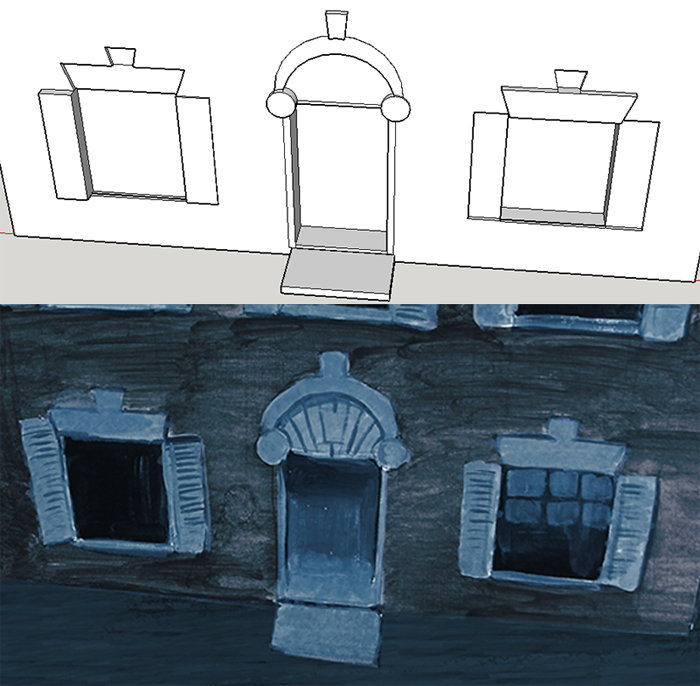

3D Model

A 3D model of the F Street tavern allowed the director to explore various angles for the exterior master shot.

Final Composite Scene

Fully animated and composited master shot.

Final Composite Scene

Animation of the F Street tavern fire, including buildings composited together based on the artworks of Alexander Rider and Anne-Marguérite Hyde de Neuville.

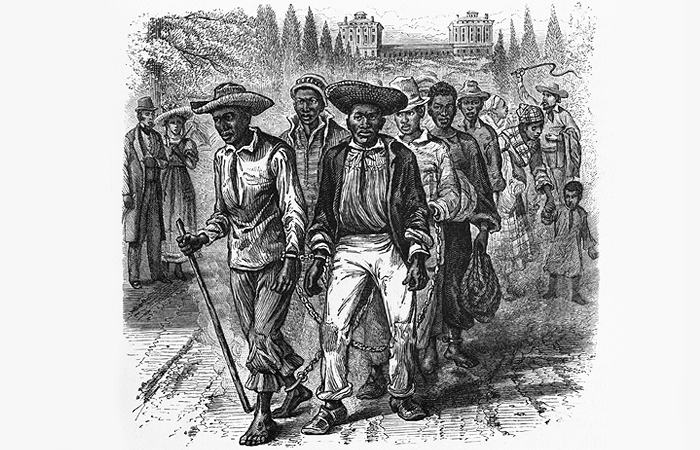

Reference Art

A wood engraving depicting a coffle of enslaved people passing the U.S. Capitol around 1815.

"A slave-coffle passing the Capitol. Washington D.C.," in A Popular History of the United States (New York: Scribner, Armstrong, and Company, 1876-1881), Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

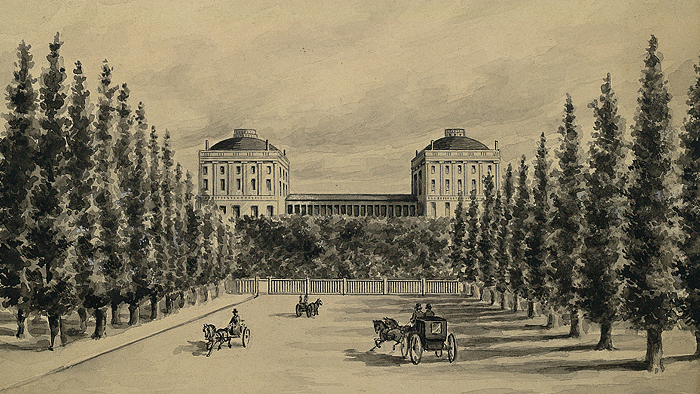

Reference Art

A drawing of the west face of the U.S. Capitol created sometime between 1814 and 1820.

"[U.S. Capitol and Pennsylvania Avenue before 1814]," Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Reference Art

A sketch of early Washington used by the team at the Imaging Research Center of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, in their virtual recreation of Capitol Hill in 1814.

Imaging Research Center, UMBC, "Visualizing Early Washington: A Digital Reconstruction of the Capital ca. 1814," YouTube, August 3, 2009.

Final Composite Scene

The final composite scene depicting the coffle on Pennsylvania Avenue walking toward the tavern on F Street.

The Exterior of George Miller's F Street Tavern

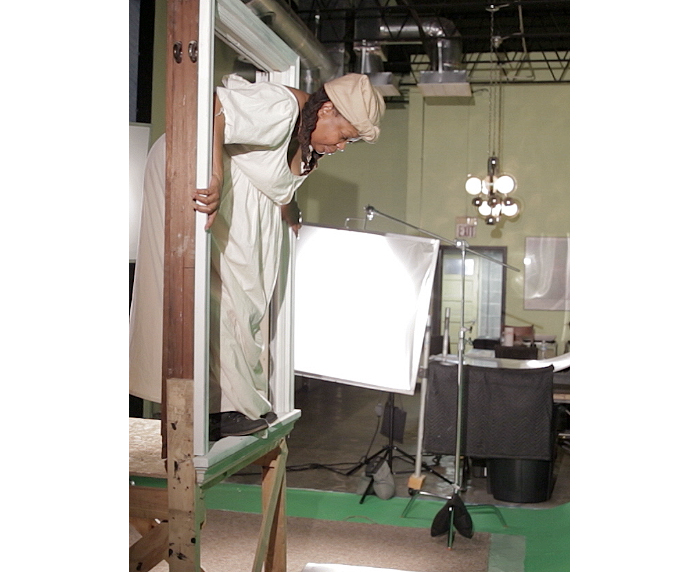

Live-Action Reference

Actress Margarett Joyner poised in a makeshift window frame at Bridge Studio in Richmond, Virginia. With a recent foot injury, she was only willing to jump down from the window once. Luckily, she was not injured again, and her apprehension made the leap that much more believable. Remember, Anna jumped from approximately thirty feet.

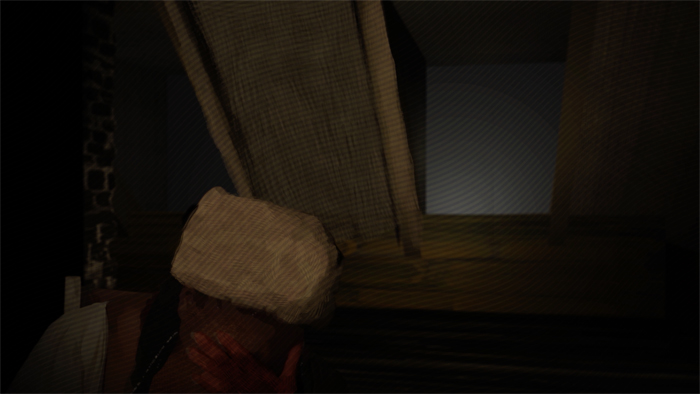

Rotoscoping Composite Scene

Rotoscoping is a form of tracing and painting each frame of live video. Animators painted approximately 18,000 individual frames for this animation. Here, Anna is painted on a green panel so she can easily be "cut out" and composited into a painted scene.

3D Model

A hand-painted background was first created as a 3D model to match the live-action footage.

Final Composite Scene

In this finished composite scene, the street, tavern, and Anna are all painted as separate layers. It took a total of 18 working hours to produce this 3 seconds of action.

Live-Action Reference

Another live-action shot of Joyner in the makeshift window frame at Bridge Studio.

Final Composite Scene

This finished composite scene is also composed of separate layers.

Inside George Miller's F Street Tavern

Reference Art

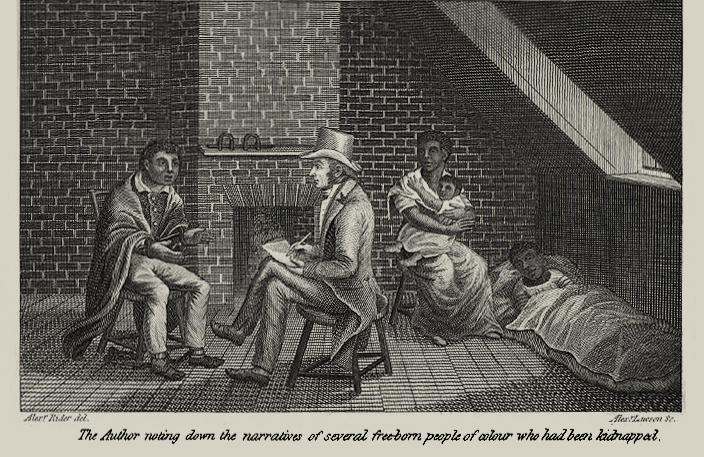

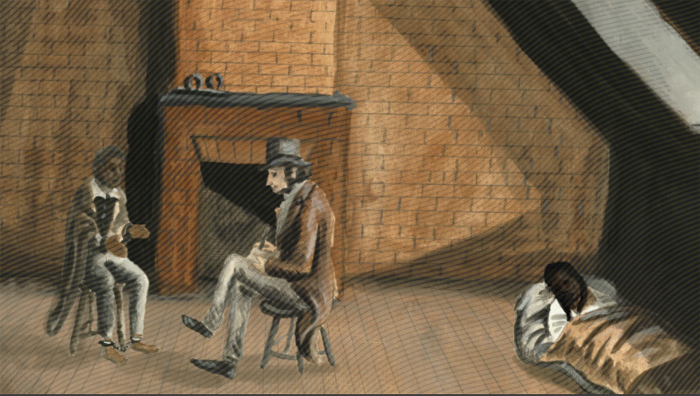

We used Alexander Rider's etching of Jesse Torrey, Ann Williams, John Paker, and Rosanna Brown from Torrey's 1817 publication, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery in the United States, as a basis for our recreation of the tavern garret. Although the image contains only a single window, we were able to determine the approximate size and location of the second window relative to other images of nearby buildings painted around the same time period.

Jesse Torrey, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery in the United States (Philadelphia, 1817), facing 46.

Reproduction

We created a reproduction of Rider's etching for the credit sequence. The decision to overlay the painted animation with an etched effect was made to give the impression of a motion-based version of the original artwork.

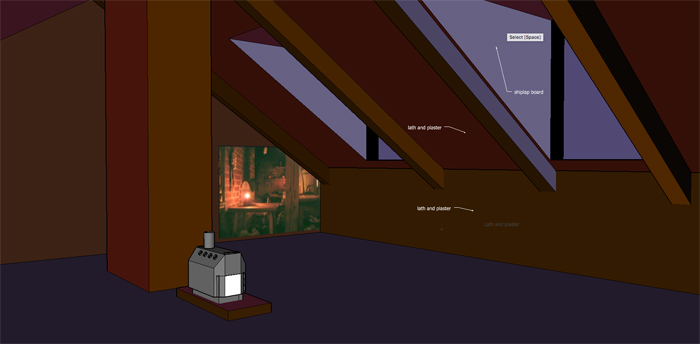

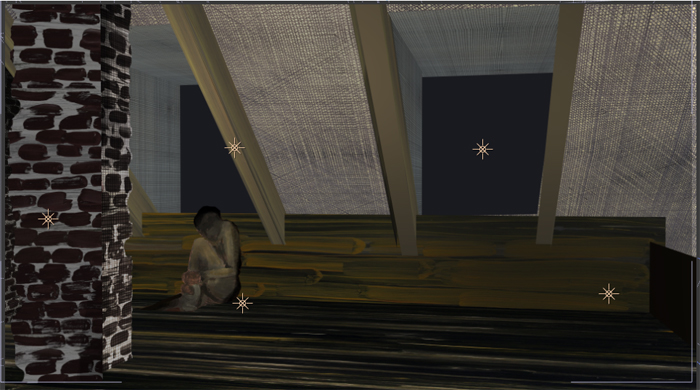

3D Model

A 3D model of the garret allowed the director to explore the various angles that Anna could tell her story from. This model includes a small stove and chimney that was later changed to a brick wall in order to be historically accurate.

Textured 3D Model

A second 3D model of the space was created in Adobe After Effects. Hand-painted and illustrated textures were applied to the walls, ceiling, and floor. Not pictured here are the various images of 19th century structures and interiors that informed how the artists recreated the animated surfaces.

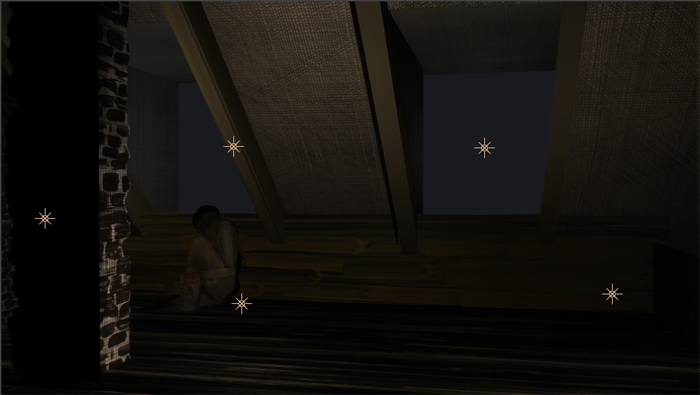

Lighting Control

Various lighting points were placed in the completed model to control and recreate lantern lighting. The changes in lighting that appear throughout the animation are made possible by controlling the lighting scenario.

Final Scene

This shot from the final sequence of the film shows the end result of the lighting control and completed modeling.